El Chaltén ‘24/’25

Arrival in El Chaltén

I left El Chaltén in 2022 knowing that I would not be back the following year. I wanted to take a break from the place to reflect in addition to pursue some career ambitions in the building space more seriously. With the latter goal in mind, I ended up working a demanding yet rewarding job for an eighteen month term, and while the job didn’t technically wrap up by the start of the climbing season in Patagonia, I had made it clear to my boss from the start that I would be heading back down in December 2024. By the Fall I was quite burnt out on my stressful sixty plus hour per week work situation and was very much looking forward to some “vacation” time in South America. A friend mentioned it was perhaps ironic that climbing in El Chaltén would be my form of stress relief, but I can confirm that it certainly was.

Climbing in Patagonia entails a lot of down time as the weather is generally awful and I was very much looking forward to a slower pace of life and zero time behind the wheel of a car. The thought of reading books again, writing down my thoughts, hanging with the community down here, exercising excessively, and eating in a way that corresponds with the previous two items, was incredibly exciting. I was mega stoked to arrive, and feelings of joy and excitement penetrated my brain during my travels as I thought about how much I love climbing in this place. I ended up rereading the entire Patagonia Vertical guidebook by Rolo Garibotti cover to cover during my travels which confirmed my psych was through the roof… Just where I wanted it.

After my last day of work but before my flight down to South America, a few friends asked me if I felt relieved for being done with my arduous work situation. My honest answer was that it didn’t feel any different so immediately after my last day. However, I do recall feeling a mental release as soon as I hopped on the third flight of my journey down and realized I was thousands of miles away from home.

Mojon Rojo

This trip was my third to Patagonia and like the previous two, I arrived mid weather window. Unfortunately, the timing worked out so that I would miss out on climbing but I thought there would be enough time to run into the mountains for a little jaunt to retaste this magnificent range before the weather turned bad.

I woke up my first morning after a short night of sleep and hiked into the mountains with the hope to climb a little formation adjacent to the southernmost peak of the Chaltén (Fitz) skyline called Mojon Rojo. I was feeling quite good on the approach and was optimistic about getting to the summit in under three hours from town but upon hitting the glacier, that quickly changed. As I began to trudge through sloppy and deep snow, it began to rain, eventually turning to sideways hail pelting my bear legs and then sideways snow, numbing my extremities. The storm had arrived, and I was nearly certain I would be bailing for the entirety of the last hour as I slowly scrambled to the summit block. I ultimately did bail just fifteen feet from the top which was being audibly hit by winds that would literally have blown me off the mountain… Classic Patagonia. I smiled, feeling content with my journey up and began the descent back down the glacier that now contained a breakable ice crust that my bear shins did not appreciate. On the way down, I asked a few different groups of hikers for food as I was dumb enough to only bring two bars and ended up coming close to bonking… classic. I had forgotten how much energy it takes to get into these mountains! The entire journey from town to town took exactly seven hours and covered just over twenty miles and six-thousand feet of elevation.

Upon arrival back to where I was staying, I linked up with my good friend and recurring El Chaltén roommate Thomas Bukowski as well as two other climbers, Austin Schmitz and Carly Kristin, who I would share a loft with for the coming week at Centro Alpino. At 4:30am, all four of us woke to the sound of an explosion. I looked out the window above Austin and Carly’s bed and saw a fiery orange color outside of the glass that indicated a fire was extremely close. It turned out the exploding item was a propane tank inside a new restaurant across the street that had literally just opened a week before. We peered out the window as we witnessed the restaurant and adjoining home become fully engulfed in flames. The raging winds blew embers into our yard at Central Alpino and the four of us stood in disbelief as a group of fire fighters and first responders attempted to extinguish the blaze and stop it from spreading. By first light, the fire had consumed all fuel sources within the structure and thankfully the fire fighters were able to contain it from spreading further despite the wind. I believe I slept for well over ten hours the next evening.

Mojon Rojo after Bailing from the Italian Pillar on Poincenot

My first and only climb with Colin Haley before this season was a complete epic where we bailed nearly four-thousand feet down the east face of Cerro Chaltén in a storm in 2022. Despite our lack of success together, he still seemed keen to climb and reached out later that year to see if I was interested in partnering up for the ‘23/’24 Chaltén season. It felt absurd to say no to such an opportunity, but I had committed to my job and felt inclined to stick to it.

I reach out to Colin a year later to see if he would be interested in climbing together for the ‘24/’25 Austral Summer season, and I was happy to find that he was still game. We discussed some loose ideas regarding objectives over the phone and agreed to commit to climbing together from mid-December through mid-February.

The day after getting back from Mojon Rojo we linked up to discuss our plans for the season and compiled a list of objectives we were interested in attempting. High on that list was the East Pillar or Sperone Degli Italiani on Aguja Poincenot which is a four-thousand foot route that I would argue is one of the most beautiful lines in the entire Massif. The feature is incredibly obvious from town and “in your face” as one hikes up the popular trail to Laguna de los Tres.

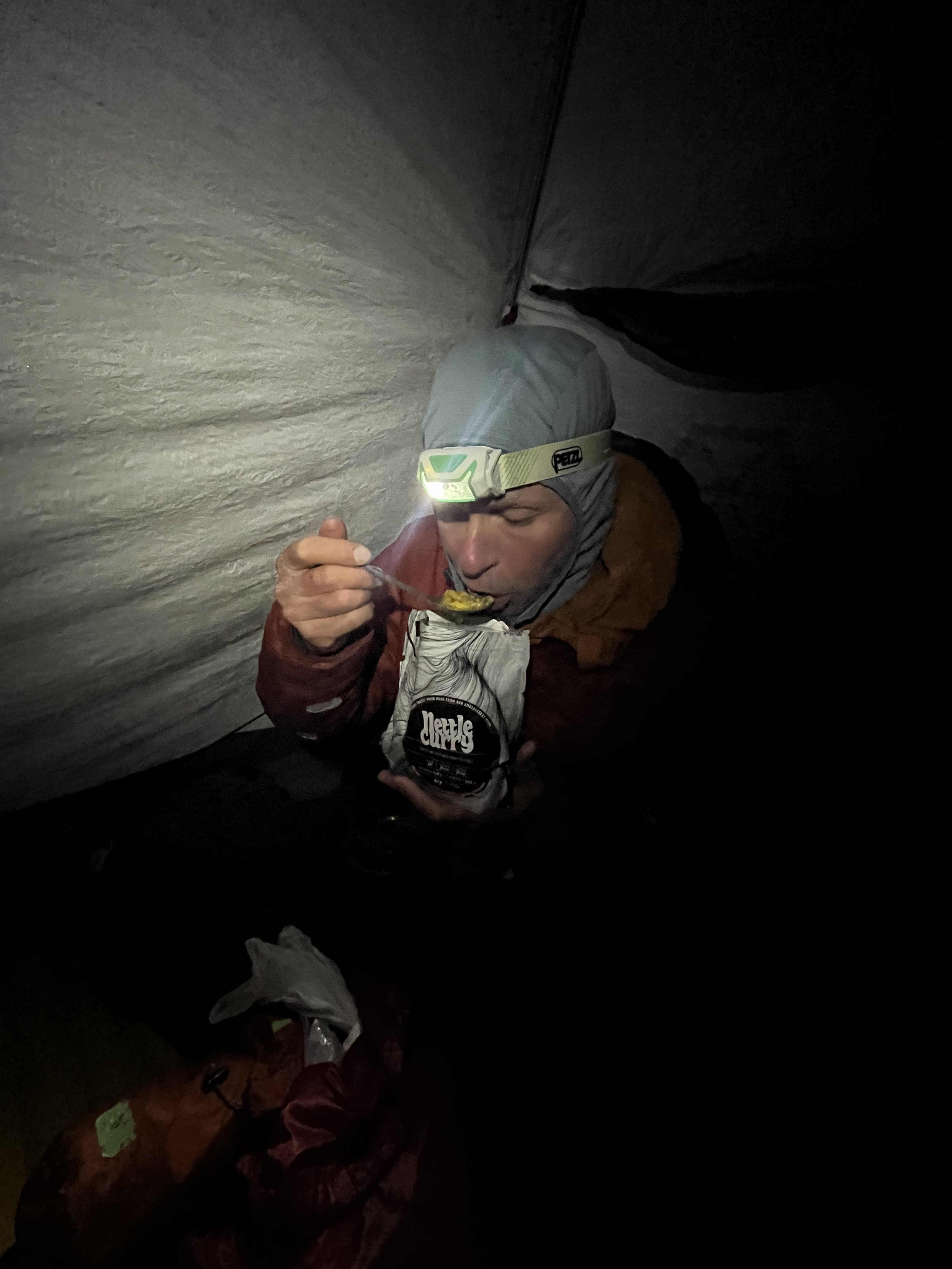

The glacier below the Southeast face of Poincenot can be a pain to cross which was a major incentive for choosing to attempt this route at the start of the season. Colin had also actually just attempted the route with Thomas a couple weeks back but only got two or three pitches up before bailing. We hiked in on December twenty-third and set up our tent on the glacier just below the massive southeast face. We woke early, traversed a steep snow slope above a massive bergschrund and started up what would break up into six pitches of moderate mixed terrain on generally abysmal rock and snow before getting to the first truly vertical rock pitch. Twelve of the next thirteen pitches contained nailing according to the topo and the plan was for me to lead all these pitches and for Colin to take the mixed terrain at the start and moderate rock terrain above.

The route was first climbed in siege style in 1986 by an Italian party to the Whillans-Cochrane, one-thousand feet below the true summit, and then finally completed to the summit by Silvo Karo and Andrej Grmovsek in 2005, it’s only true ascent. It clearly doesn’t get much traffic, likely due to the number of aid pitches but we had assumed they would go quickly with modern tactics. As I arrived at the top of the snow ramp which marks the start of the aid climbing, I was surprised to observe that the entire first pitch was soaking wet and the very first move would require me to hammer in a piton. I hammered in some beaks, clipped some drilled pitons, and pulled some exciting face moves on wet flakes, before coming to a blank section of rock.

After just a few seconds of searching for a placement, I noticed an old bolt sleeve in the rock but with a missing bolt and no threads protruding from the flush face of the rock. Hmmmm… I was not expecting to come across such a thing. Puzzled on how to get past this section, I eventually decided to use a #2 Black Diamond Pecker to hook a flake of rock in attempt to clip the next drilled piton being that I brought no real hooks. The flake was small but looked solid enough. It held my weight as I committed to my ladders but just when I was preparing to top step, the rock broke and I fell. My dynamic daisy chain was clipped into a beak just below and I fell onto it just as the rope came tight. It turned out to be a very comfortable fall and part of me was glad that I forgot proper static cord that I typically prefer to make my daisies out of.

I eventually made it past the sleeve using some diagonal top stepping creativity and continued hammering in more pitons before coming to a second bolt sleeve with a missing bolt. Dang! The pitch was rated A1 meaning it was supposed to be easy, but I felt quite defeated and humbled. The second bolt was intended to be used to pendulum into a different crack system and while it did appear possible to bypass the second missing bolt by using a thin piton placement in bad rock, my appetite for this type of climbing and potentially more missing bolts had soured. I told Colin that I thought we should bail, and with that, we agreed to go down. It turned out the weather that morning was worse than forecasted and with the clouds moving quickly above Poincenot, it was a convenient excuse to blame our bail on the weather as Colin and I both felt that even if we were to get through the steep headwall, it would likely be too windy to summit. It no doubt was not the weather that forced us to go down, but it did make the decision much easier.

As I lowered back down to the top of the snow ramp, I fixed a piece of amsteel on a drilled piton above the first bolt sleeve as well as a second piece through the first beak section to make it easier to climb through if we were to go up again. We decided to rappel directly down the steep face below the top of the snow ramp instead of reversing course down the ramp proper. Colin went first and as I followed these two full sixty meter straight vertical to slightly overhanging rappels, I felt some form of discomfort and fear. Luckily this would not occur again during this trip, but this eerie feeling was quite a welcome to Patagonia and reminded me that I was a bit rusty on steep mountain terrain.

We reached the snow slope above the large bergschrund and began to descend loose and sloppy snow. I suggested we make another rappel to go straight over the bergschrund as opposed to traversing above it. Colin didn’t seem excited about the idea, but we were in no rush, and it was obvious I was slower and less comfortable on sloppy steep snow than he was, so he agreed. We made it back to our tent in the late morning, packed up and texted Rolo to see if we could get any information on the weather window coming in a couple of days. During our rappels, I had suggested we go for a consolation summit attempt of Mojon Rojo and while Colin first appeared reluctant, upon getting past the serious part of the glacier, I was able to convince him. We romped up the peak with big smiles on our faces and literally raced down the glacier in a full sprint back to where we stashed our gear. We made it back to town in the evening and peaked at the forecast to find that an even better weather window was just around the corner. Perhaps it was for the best that we did not succeed on Poincenot.

I hope and expect to see this line repeated in the coming years. The rock looks quite good above where we bailed, and I think it would be a very fun outing for those who can do it in a single push. For those interested, I recommend bringing beaks, hooks, and threaded rod (potentially of multiple thread pitches) hangers and nuts for (I assume) eight millimeter bolt sleeves.

Southeast Ridge of Cerro Torre

This better weather window around the corner resulted in a successful summit of Cerro Torre via the Southeast Ridge which is the modern version of the “Compressor Route.” I wrote a separate blog post about this climb that can be found here: SE Ridge of Cerro Torre

El Corazon Attempt Two

Two years ago, Colin and I attempted to climb the four-thousand-foot-tall east face of Cerro Chaltén (Fitz Roy) via a route called El Corazón, making it over ninety percent of the way to the top before a storm forced us to bail down (Read that trip report here). We were both interested in getting redemption on this line and just six days after summiting Cerro Torre, we found ourselves camped below the east face, feeling optimistic that we would snag an ascent of both Cerro Torre and Cerro Chaltén in a single week. Well, I can’t speak for Colin, but conditions were significantly better than our first attempt and we already knew nearly the entire route. I was feeling confident we could even make it to the summit before dark. Other than the temperatures being quite chilly, the first eight pitches went smoothly, and I was certain we would make it to the top in quick time.

We arrived at the base of a soaking wet pitch of aid climbing called the Aquarian roof towards the end of Colin’s first block and as he prepared to climb it, we realized that the rock at the start had shifted since our last visit. A ten meter tall, twenty centimeter thick flake had detached from the wall and shifted outward. Perched above it was a second human sized flake. If we were to continue up, both would have to be climbed which made the decision to go down quite easy.

We reviewed photos taken from two years prior and confirmed our observations before unfortunately having to rappel down a separate line from our previous bail resulting in us having to leave additional cordage and carabiners. We hiked back to town in perfect weather, stopping so that I could take a quick dip in Laguna de los Tres.

Good weather is precious in Patagonia and there is certainly a part of me that felt bummed that our attempt was thwarted by a factor out of our control. However, this was a good reminder that the mountains contain unknowns and there is no such thing as a wasted weather window. Uncertainty is part of the appeal of alpine climbing and each bail, regardless of size, is a learning opportunity.

The route adjacent to El Corazón called Royal Flush also had a rock fall event on the opening pitches in the past five years. The rock below the snowfield on the buttress of the east face of Fitz seems unstable and for those interested in accessing both Royal Flush and El Corazón, the best way appears to be to come in from the left via the Pilar Este.

Aguja Bifida

Towards the end of the Torre valley is a prominent but seldom climbed peak named Aguja Bifida. The coming weather window after our El Corazón attempt was looking marginal with cold temperatures and high winds forecasted, so Colin and I estimated an attempt on this relatively low elevation, wind protected, and sunny northeast aspect would be a wise choice.

We hiked to the base of the route over a long day and awoke the next morning to a beautiful sunrise before meandering through steep and exposed snowfields as we approached vertical rock. My pace slowed relative to Colin’s as we traversed above large crevasses and steep rock, and my ego eventually relented as I requested to rope up for the final section. Perhaps I should have brought real boots. Colin led the first half of the route, often chopping ice out of cracks to make upward progress. I followed the opening rock pitches in gloves due to the cold, and for the first several hours of the day, I had a gut feeling we would be bailing. Eventually the sun came out, the cracks became less icy, and for a few pitches, it appeared we would be climbing perfect splitters to the top.

As I took over the lead, the rock quality degraded and wind speeds increased as I climbed through a series of icy chimneys to the summit ridge. Upon arrival at a spacious belay ledge with a view of both Cerro Torre and Cerro Chaltén, I watched Cerro Torre get engulfed in clouds that would remain for days in the time it took me to belay Colin up the pitch. With less than a rope length to the summit on this two-thousand-three-hundred-foot route, we briefly pondered going down, before Colin took the lead and quested up two final short but wild and windy pitches to the top. The weather window was clearly closing, and we began our descent on the wind protected side of the mountain back to the glacier, arriving at our tent in the rain after having to cut our rope on the third to last rappel.

Success in the mountains down here often relates to reading the weather correctly and dialing in logistics/strategy more so than pure climbing talent. The added complexities are partially what make this place so appealing to me and during this particular outing, it felt like we nailed it.

We woke the morning after in the rain and packed up our wet clothing and gear as quickly as possible. The rain continued for most of the day but it was the wind that truely made the hike back to town brutal. We would occasionally have to kneel down in order to avoid being toppled over by the winds and at one point, I managed to snap my trekking pole. We arrived back in El Chaltén quite wet and happy to be in civilization.

West Face of Guillaumet

Thus far this season, a new weather window was consistently appearing less than a week after the previous one ended which is quite incredible for Patagonia standards. None of them were truly exceptional except for the one we climbed Cerro Torre in, but the high frequency was still a gift. Six days after Bifida, Colin and I hiked out to Piedra Negra to climb on the west face of Guillaumet during a small but certainly climbable window. Compared to our four previous missions to the mountains, this one felt quite civilized being that we were planning to freeclimb rather than pulling on gear to get up as quickly as possible in addition to not camping on a glacier. We enjoyed the benefits of a short approach, cached gear, not having to melt snow for water, and even sleeping in till a relatively late time of 5:20 am. The day was going smoothly through the end of our fifth pitch when a rock, roughly the size of a human head, randomly released from above, ricocheted off the wall and hit Colin in the arm.

I was in the process of building an anchor at the top of the pitch and was out of view of Colin. I heard a yell but could not do anything at that moment except for hope he was not seriously injured. I shouted down asking “are you okay?!” and got back “give me a second!” Waiting that second felt like minutes but really must have been five to ten seconds. Colin informed me he was injured, was unsure how serious it was, and was in the process of evaluating it. I had a feeling we would be going down and started rigging a rappel anchor out of two nuts equalized with a sling. A minute or two later, Colin informed me we would in fact be going down and I subsequently did two single rope rappels to get back to him.

The situation was not as serious as I had initially feared, and Colin was able to complete all the necessary tasks to get himself down the mountain as I rigged the rappels and pulled the ropes. This route is not typically used as a regular rappel line and for good reason as I found it challenging to avoid the rope getting caught. I had to reclimb two short sections to retrieve the rope and once cut the tag line but overall, the rappels went okay, and we made it down with plenty of time left in the day to hike back all the way out to El Pilar by Rio Electrico.

Cerro Nire to Cerro Techado Negro (The Techado Round)

While bailing is certainly part of the game climbing in the mountains, one of the biggest bummers of not reaching a summit in general this season is my inability to eat ice cream from the local ice cream shop Domo Blanco. In previous seasons, my fellow Californian climbers and I would splurge at Domo Blanco, occasionally eating multiple ice cream cones per day. This season, due to both the new currency exchange rate and my desire to stay fit, I have made a rule that I am only allowed to eat one ice cream cone per summit attained. For those curious, I define a summit as any peak on the final page of the Patagonia Vertical guidebook with an upside-down ice cream cone (aka triangle) adjacent to the name. If one were to climb the Fitz traverse, they would get nine ice cream cone tokens but if one were to climb the Torre traverse, they would only get three ice cream tokens as Puna Herron is not considered a summit. The easiest way to obtain an ice cream token from town would be to hike up Cerro Rosado.

Two days after getting back to town from Guillaumet, a smaller weather window appeared in the forecast, and I was still keen to get out even though I was without a partner. Colin’s arm was still a bit too banged up to go climbing and luckily for him, the window wasn’t a bad one to miss. The mountains were plastered with snow at higher elevations and the window was essentially just a half day endeavor with high winds and more snow expected in the afternoon. Thomas and I agreed to link up this round, which I was quite excited about. As we were deciding what to do, our neighbor from the adjacent flat Fabi Hagenauer asked if he could join and we agreed! I had no idea how fit or good a climber Fabi was, but my assumption was that he was dialed.

We consulted Rolo for ideas, and he suggested a link up of some of the lower elevation mountains in the range that starts by going up the southeast ridge of Loma de las Pizarras then hits both summits of Cerro Nire and finally Cerro Techado Negro. Rolo certainly knows how to provide quality recommendations because if successful, I would bank three ice cream cone tokens at Domo Blanco. This exact linkup had never been done before but it is certainly not cutting edge or particularly noteworthy. It is essentially the mega sit-start to the Moonwalk Traverse as it travels the continuation of the ridge of the Fitz skyline southeast past Aguja de la S and Mojon Rojo to the valley floor.

Thomas went to bed feeling a bit sick and sadly opted to stay home when we woke. Fabi and I left town at first light and hiked up to Loma de las Pizarras via a beautiful and mellow low angle ridge. From there the scrambling began as we ventured along an often knife-edge ridge to the east summit of Cerro Nire. We climbed over to the more frequently traveled west summit of Nire, roping up for the final ten meters before rappelling down to the east, romping up a snowfield, and scrambling to the top of Techado Negro. We descended back to Laguna Sucia, went for a swim, and hiked back to town making it in a leisurely thirteen hours round trip. The weather turned out to be even better than forecasted and the views from this ridge were mind-blowingly beautiful throughout the course of the day. I very much recommend this traverse to those looking for a fun day of mountain scrambling when the weather is just okay. Fabi named the traverse the “Techado Round.”

Town Window

The frequency of weather windows changed after the Techado Round and we began what Thomas dubbed a “town window,” or window of time in which we would be hanging out in town because the weather was not good enough to go out into the mountains. We would check the forecast multiple times per day and speculate on far out systems with optimism, but things were certainly not looking hopeful.

Due to the uncertainty, Thomas and I thought it would be wise to escape up to Bariloche and climb in Frey for a week, but I ultimately bailed on the plan because of some work commitments. By this time, Jenny Abegg had arrived as my new loft mate and instead of travelling so immediately, we decided to use a brief day of slightly better weather to go on a 50k run around Cerro Milanesio. This was my first time running such a distance which I was told is an ultramarathon, but I struggle to consider it as such because I spent so much of those miles walking! I honestly had a blast as we ran, walked, waddled, bushwacked, climbed, and slid through various mediums of earth while conversating for the entire duration. About halfway through the day as both Jenny and Thomas recounted stories of their one-hundred mile races, I informed them both that ultra running will not be my thing. I do see the appeal of running, and I would not be opposed to doing more ultras, but I just don’t see myself getting too deep into it and I am certainly not interested in the racing component. But who knows? Perhaps I will rethink these words one day, which is part of the reason I want to write them down. The best part of the day besides observing the incredible views was spending quality time with Thomas and Jenny and that alone made this little adventure a special one.

Frey

The day after our run, the forecast in Chaltén still looked abysmal so Thomas and I made the call to head north to Frey. Feeling pessimistic about the future of the weather and also feeling lovesick to get back to my partner, I opted to bring all the gear I was planning to take back to the states and fly back early unless in fact a mega weather window peaked out of the blue upon returning to civilization after Frey. Colin had made the call to run away from the bad weather early as well so if I were to come back, the plan was to climb with Thomas. Thomas and I originally looked at flying up to Bariloche but our friend Bernie Ertel, who would be joining us, knew a local driving up named Martin Lopez Abad. Martin and his childhood friend Mateo picked us up in a minivan late one morning and we started our long drive up Route 40 to Northern Patagonia. Like my first trip up Route 40, three years back, this one turned into quite an adventure after our front axle exploded at one am due to an impact with a pothole. A string of rides, buses, and random bivies eventually led us to the kind folks at the Patagonia Inc. store in Bariloche where we showered at Casa Frey, repacked, and refueled before hiking into Refugio Frey for five days.

The bad weather seemed to follow us, as during my first morning in Frey, I woke up too tired from my travels to seek shelter as I got rained on for two hours in my sleeping bag. The wind and cold persisted for a few days and forced us to bail on overly ambitious objectives more than once, but we still got in some quality climbs. The rock climbing in Frey contrasts significantly with that of El Chaltén, being far more thought-provoking, engaging, and slower in general. While the routes are relatively short, the quality of climbing, the hang, and aesthetic of the place make Frey very worthy. One way to put is that Frey is El Chaltén as Joshua Tree is to Yosemite.

The weather in El Chaltén stayed terrible for the remainder of the season. There were some periods of good weather, but the mountains were so plastered in snow during those times that very few significant climbs were accomplished. I luckily was able to change my flight free of charge since the airline had modified the flight time by just a few hours shortly after I purchased it six months earlier. I flew back to the states on February eleventh, feeling happy with my season, grateful for my partnerships/friendships forged down here, but still hungry for more. The climbing in the Chaltén Massif is as good as it gets in my opinion, and I certainly will be back. Perhaps next year, or the year after, or the year after that. Who Knows?